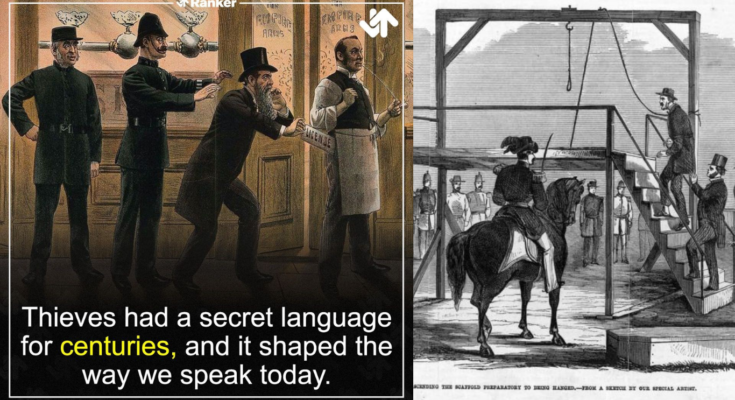

A Thief’s Worst Fate Was To ‘Ride A Horse Foaled By An Acorn’

A Thief’s Worst Fate Was To ‘Ride A Horse Foaled By An Acorn’

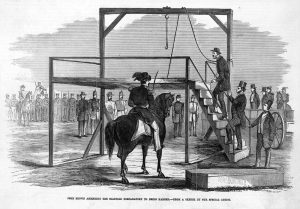

Thieves’ cant contained multiple terms related to getting caught. Rustlers worried about getting sent to the “picture frame” (the gallows), judges were called “fortune tellers,” and all thieves fretted over getting “frummagemmed” (hanged).

To climb the gallows was to “ride a horse foaled by an acorn.”

Photo: Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

Martin Luther Was A Personal Victim Of Thieves’ Cant

Martin Luther Was A Personal Victim Of Thieves’ Cant

Reformation leader Martin Luther was allegedly cheated by thieves speaking a secret dialect. In 1528, Luther wrote the preface for a German edition of a text called Liber Vagatorum (later called the Book of Vagabonds and Beggarsin English). The book contained a glossary of thieves’ cant, explaining the coded language to readers.

Luther claimed he had been “cheated and befooled by such tramps and liars more than [he wished] to confess.” To Luther, the slang was proof of “how mightily the devil rules in this world.”

Photo: GalleriX / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

Rogues Took A ‘Fight Club’-Style Oath

Rogues Took A ‘Fight Club’-Style Oath

According to multiple popular books, thieves – often referred to as rogues – took an oath when they joined an underground society of outlaws. In Richard Head’s 17th-century book, The Canting Academy, he described the oath: Thieves chose nicknames and consciously forgot their birth names before swearing to be a “true Brother” and obey “the commands of the great tawny Prince.”

This vow also mentioned their coded language and its enforced secrecy: “I will not teach anyone to Cant, nor will I disclose ought of our mysteries to them, although they flaug me…”

Photo: Unknown / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

Jewelry Thieves Stole ‘Chunks O’ Gin’ And ‘Chunks O’ Brandy’

Jewelry Thieves Stole ‘Chunks O’ Gin’ And ‘Chunks O’ Brandy’

Unsurprisingly, thieves used code names to discuss the items they snatched. Jewelry thieves might be after a “chunk o’ gin” (a diamond) or a “chunk o’ brandy” (a ruby).

Sapphires were referred to as “berry wine,” while the less glamorous “Irish apricots” were potatoes.

Photo: Pieter Brueghel the Elder / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

‘Badgers’ Terrorized People Near Rivers

‘Badgers’ Terrorized People Near Rivers

According to a 1760 dictionary of thieves’ cant, innocent people were well-served to avoid “badgers” – a slang term for “a crew of desperate villains, who rob and [slay] near rivers, and then throw the… [remains] therein.”

Thieves’ cant dictionaries promised to expose a secret world, simultaneously entrancing and repulsing readers. One glossary of the cant promised that readers would find “the Devil’s cabinet, opened” inside.

Photo: Unknown / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

Modern Words Like ‘Phony’ Originated From Thieves’ Cant

Modern Words Like ‘Phony’ Originated From Thieves’ Cant

Several modern words can be traced back to thieves’ cant, including the word “phony.” As early as 1770, English thieves were practicing a ruse called the “fawney rig.” In this scheme, a rogue would drop a cheap ring in front of their mark. They would then offer to sell it for less than its supposed worth – although the jewelry’s true value was next to nothing.

The fawney, or ring, was a fake used to trick the mark. Thieves may have adapted the word “fawney” from “fáinne,” the Irish word for ring.

Photo: Emanuel Spitzer / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

Some Thieves’ Cant Terms Seem Completely Indecipherable

Some Thieves’ Cant Terms Seem Completely Indecipherable

If a 16th-century rogue mentioned “Oliver,” he was using thieves’ code to reference the moon. Thieves’ cant contained some even more befuddling code words: “Marriage-music” meant crying children, “rhino” was code for money, and rogues called eggs “cackling farts.”

Photo: loki11 / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

‘Swindler,’ ‘Pigeon,’ And ‘Grease’ All Come From Thieves’ Cant

‘Swindler,’ ‘Pigeon,’ And ‘Grease’ All Come From Thieves’ Cant

Many modern words related to lawbreaking come from thieves’ cant. A “swindler,” for example, refers to a liar or cheat in modern English, which is exactly how outlaws used the term centuries ago. Similarly, the word “pigeon” is still used to describe someone who easily falls for a con.

Thieves’ cant also turned “grease” into a term for bribing someone and popularized the phrase “left in the lurch” as an idiom for betrayal.

Photo: Internet Archive Book Images / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

Translations Of Thieves’ Cant Became Wildly Popular

Translations Of Thieves’ Cant Became Wildly Popular

Readers were entranced by the idea of a secret villainous society operating out in the open. In 1566, Thomas Harman published A Caveat for Common Curistors, in which he claims that rogues used a secret language called thieves’ cant. Right in front of upstanding citizens, these ruffians laid out their unlawful schemes.

Harman claimed his book was “for the utility and profit of his natural country.” According to Harman, spreading information about thieves’ cant was “good, necessary, and [his] bounden duty,” because he was showing readers “the abominable, wicked and detestable behavior of all these rowdy, ragged rabblement of rakehells.”

The popularity of Harman’s book incited a trend of copycat glossaries, dictionaries, and pamphlets on thieves’ cant. As late as 1859, a New York police chief named George W. Matsell published The Rogue’s Lexicon so readers could better understand outlaws.

Photo: British Library / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

The English Referred To Thieves’ Cant As ‘Peddler’s French’ To Insult France

The English Referred To Thieves’ Cant As ‘Peddler’s French’ To Insult France

In England, thieves’ cant had another name: peddler’s French. However, this nickname didn’t mean the dialect originated in France. In reality, it was a subtle way for the English to insult the French. Similarly, Italians called syphilis “the French disease,” while the French attempted to rename it “the Italian disease.”

Scholars disagree on the origin of thieves’ cant, and its true roots are still largely unknown. Researchers have detected French, English, Italian, Russian, Latin, Yiddish, and Romany influences within the slang terms.

Photo: Unknown / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

Incarcerated People In England Are Bringing Back The 500-Year-Old Slang

Incarcerated People In England Are Bringing Back The 500-Year-Old Slang

English prisoners revived thieves’ cant in 2009 to smuggle controlled substances into penitentiaries. The criminals called dope “chat” or “onick,” while crack was “cawbe.”

According to an anonymous source working at HM Prison Buckley Hall in England:

This is the most ingenious use of a secret code we have ever come across. Elizabethan cant was only used by a tiny number of people and it is quite amazing that is has been resurrected in order to buy [substances]. Some inmates will try anything to get contraband [behind bars].

Thieves’ Cant May Have Been Created By Fiction Authors

Thieves’ Cant May Have Been Created By Fiction Authors

Many scholars argue that the secret dialect outlined in Thomas Harman’s 16th-century dictionary was fabricated. Harman may have incorporated some actual slang in his book, but some sections were likely the product of his own invention. His stories about clever rogues, for example, were simply lifted from folklore.

Authors like Charles Dickens later used thieves’ cant in their novels to make their tales seem more realistic, although Dickens almost certainly relied on slang dictionaries for his books. Many thieves’ cant dictionaries simply borrowed from earlier versions, potentially repeating fabricated words.

However, author Maurizio Gotti notes that several court records mention thieves’ cant, indicating that at least some words were legitimate.